Imitation Activity #3

Last week, we talked about persuasion and how to use enthymemes. Today, we will do some practice and then start employing ethymemes in our own writing. First, though, here’s what we talked about last week.

Enthymeme: A deductive argument having a proposition that is not explicitly stated; esp. a syllogism with an unstated premise. (OED)

In other words, a syllogism in which the major premise, or common knowledge, is not stated. The conclusion might also be left out so the reader can draw their own.

Syllogism: Logic. An argument expressed or claimed to be expressible in the form of two propositions called the premisses, containing a common or middle term, with a third proposition called the conclusion, resulting necessarily from the other two. (OED; my emphasis)

Let’s look again at Aristotle’s famous syllogism:

- All men are mortal. < Major Premise

- Socrates is a man. < Minor Premise

- Therefore, Socrates is mortal. < Conclusion

Here’s the formula for that and all other syllogisms:

- A is B. (Or, B is A.)

- B is C.

- So, A is C.

The enthymeme is usually, but not always, the minor premise or B is C. So, the enthymeme for Aristotle’s syllogism is, “Socrates is a man.” Why does that work? Because, if you want to convince people that Socrates is mortal (A is C), all you have to do is prove that he is a man (B is C) based on the common knowledge or assumption that all men are mortal (A is B).

Now, we’ll start by using this formula to determine our audience’s commonly held assumptions.

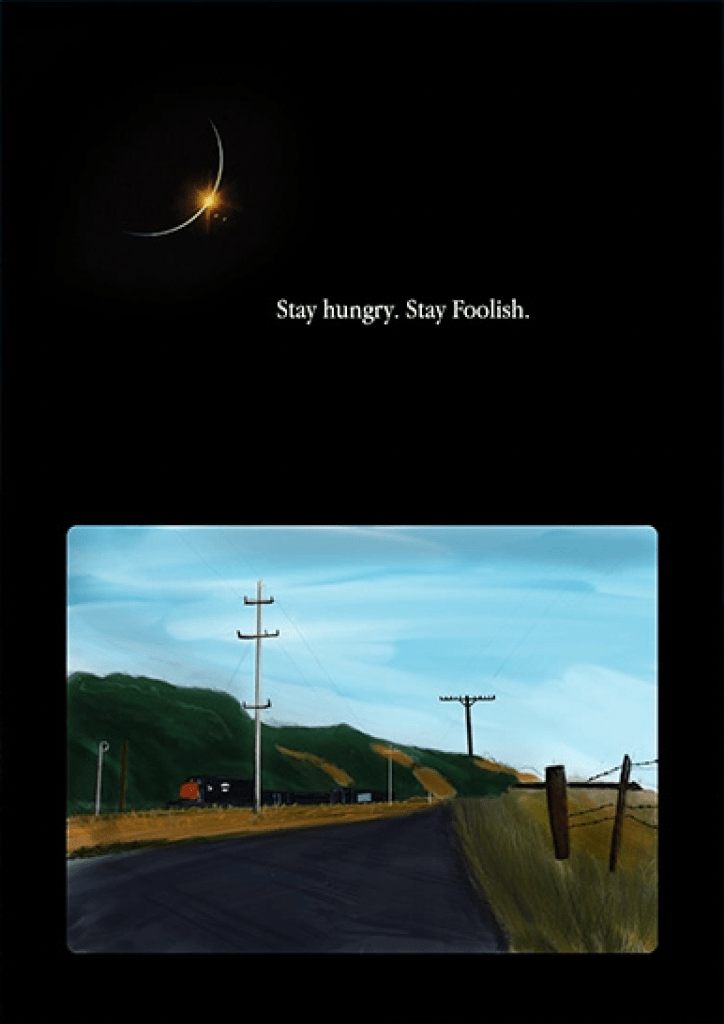

For this step, use the syllogism template above to deconstruct an enthymeme. I have provided step by step instructions, but this task might still be difficult. Deconstructing enthymemes is like a puzzle: It might hurt your head the first few times, but once you get the hang of it, you'll have an almost intuitive sense of how different pieces fit together. This one even stumped me for a moment. Just take your time and be patient. I went back to the literacy narrative examples you all posted and pulled a complex but pertinent enthymeme for the tech field. Steve Job's final piece of advice, from the last issue of a colleague's tech publication, in his 2005 Stanford Commencement Address is "Stay hungry. Stay Foolish." It's unexpected advice coming from him, so lets deconstruct it. We'll take this as his minor premise, so it contains B or C, or maybe both. It might help to look at the whole piece from the The Whole Earth Catalog (right). To deconstruct this enthymeme, we might need to translate "Stay hungry. Stay Foolish." into more conventional terms. Perhaps something like, "Pursue your passions and take risks." Go through the following steps to think through the enthymeme. You do not need to submit any notes, but you may need to write ideas down, even wrong ones, in order to come to the right answer. - If "passion and risk" are our B, what is C? Complete the Minor Premise. You don't need to know anything about Steve Jobs or his speech to figure that out. Based on the image above, what do passion and risk lead to? - Now that you have B & C, what is A? What is the conclusion Jobs wants us to come to on our own? Remember, in a syllogism, the Minor Premise must distribute. Therefore, if "pursue your passions and take risks" is C, then it is part of our Conclusion also. What is the goal of this kind of argument? What should we take away from it? What action can we take? - Now put it all together. You have A and C, so what is the common assumption or knowledge that Jobs believes he shares with his audience here? What is the Major Premise? To answer the question, use the syllogism template to write out the full syllogism.

Now, we get to imitate and apply all that work we just did! This week, we're working on research proposals, so find a research proposal that someone has written for your field of interest. You might find a more traditional abstract or research proposal, like for an academic project in engineering or pyschology (or really any field). Or, you might find a business-oriented proposal, like a grant proposal or a spec for a new client. Either way, you will be able to imitate it for this assignment and to write your own proposal tomorrow. 1. Most a link or citation for your proposal. 2. Identify an enthymeme. We've already looked at several, so you should have some sense of what that looks like. It might still be tricky though, so, again, be patient. Remember, the enthymeme will probably be a key argument, and it will leave out a shared assumption that allows the reader to understand, and hopefully agree with, the argument. Copy and paste the enthymeme here. 3. Now, use the syllogism template to deconstruct your enthymeme. You already have B or C or both. Now, figure out the rest. What conclusion do you come to? What, then, is the shared knowledge or assumption?

You can now see how an enthymeme might be used in a research proposal, or in persuasive writing more generally. Complete these three steps to write your own syllogism: 1. Determine the conclusion you would like your reader to come to after reading your research proposal. (Basically, you want them to accept the project, but it will need to be more nuanced than that. 2. Determine the Major Premise that you share with your reader. As we saw with Deloitte, many companies state these premises outright on their websites. You might still have to do a little bit of deconstruction though to figure out what values underlye their claims. 3. You now have your Major Premise (A is B) and your conclusion (B is C). Use the syllogism template to write out the full syllogism. 4. Then, use your Minor Premise (B is C) and the example you deconstructed in the previous step to write a convincing draft of an argument for your research proposal. Why should this company take you on to do this project?